Why EU Commissioners are Banned and why Infrastructure Is the Real Issue

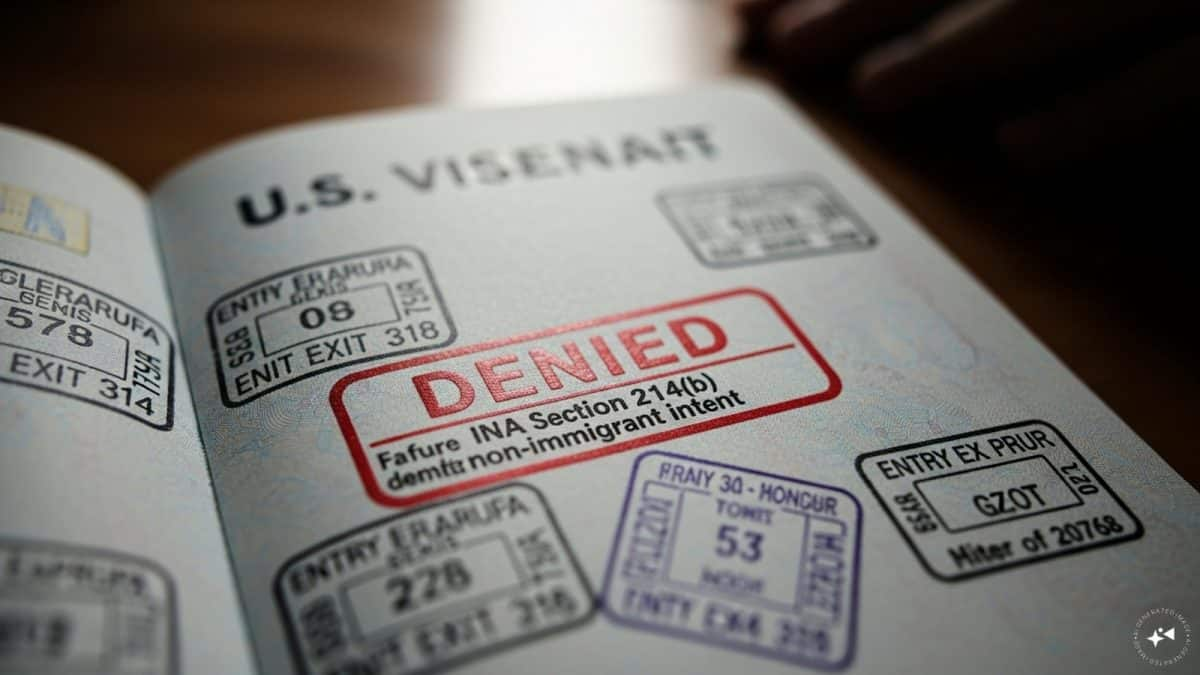

When the United States recently denied visa access to Europeans connected to a former EU Commissioner over the enforcement of digital regulation, it felt like an overreaction. But it was not irrational. It was strategic. Digital power is geopolitical power, and those who control the infrastructure reserve the right to apply pressure when their business models are threatened.

This moment should not surprise us. Tim Wu, in his book The Age of Extraction, describes how modern power no longer relies primarily on producing goods, but on controlling systems. The dominant players don’t create value so much as extract it. From data, from attention, from dependence. Extraction works best when alternatives are scarce and exit costs are high. That is exactly the position Europe has placed itself in.

For decades, the EU has focused on regulating markets while allowing the underlying digital infrastructure to consolidate elsewhere. Cloud computing, AI platforms, collaboration tools, developer ecosystems, most of the core layers of Europe’s digital economy are owned, operated, and governed outside the EU. As long as geopolitics were calm, this imbalance felt manageable. But extraction models reveal their true nature under pressure.

Wu’s central insight is that extraction is not neutral. It reshapes incentives, concentrates leverage, and eventually turns infrastructure into a tool of control. The visa bans, the trade threats, the lobbying pressure against European digital laws , these are not anomalies. They are predictable outcomes of a system where Europe consumes but does not own the stack.

Europe knows the risks

What makes this moment critical is that Europe already knows the risks. The GDPR, the Digital Services Act, the Digital Markets Act, and the forthcoming AI Act are all attempts to limit extractive behavior. They push back against surveillance business models, monopoly rents, and algorithmic opacity. But regulation alone cannot counter extraction if the technical foundations remain extractive by design.

You cannot meaningfully regulate an ecosystem you do not control.

This is where open source stops being a philosophical preference and becomes a strategic necessity. Open source breaks the extraction cycle at its root. It allows infrastructure to be inspected, modified, forked, and hosted locally. It replaces dependency with optionality. It turns users back into participants.

And contrary to the persistent myth, Europe is not late to this game.

Across the EU, open-source alternatives already exist at nearly every layer of the stack. European cloud providers run open infrastructures that can be audited and self-hosted. Public institutions increasingly rely on open collaboration tools rather than proprietary SaaS platforms. Open databases, open automation frameworks, and open identity systems are already in production use. These systems may lack the marketing budgets of hyperscalers, but they offer something far more important: structural independence. An analysis by the Elcano Royal Institute, a respected European think tank, argues that investing in open source software can strengthen Europe’s autonomy and reduce dependency on proprietary vendors. The study suggests that increased open-source investment could measurably boost European GDP and stimulate startups.

AI is often portrayed as the ultimate domain of hyperscale extraction. Massive models, massive data, massive compute. But this too is misleading. Open-weight AI models can be trained, fine-tuned, and deployed entirely within Europe. They can be aligned with European law by design, not retrofitted through compliance layers. They can be audited for bias, secured against misuse, and governed transparently.

In Wu’s terms, this is the difference between an extractive system and a generative one. Extractive systems centralize power and monetize dependence. Generative systems distribute capability and lower barriers to entry. Europe’s economic and political values align far more closely with the latter — yet its infrastructure choices still reflect the former.

The real danger of hyperscale dominance is not cost or efficiency. It is leverage. When a handful of firms control cloud access, AI tooling, identity layers, and developer ecosystems, they gain the ability to influence policy indirectly. Regulation becomes a negotiation. Enforcement becomes conditional. Sovereignty becomes theoretical.

From propriety to open

Europe does not need to retreat from global technology, nor does it need to “ban” foreign platforms. What it needs is a default shift: from proprietary to open, from centralized to federated, from extraction to participation. Public money should build public infrastructure. Compliance requirements should privilege self-hostable, interoperable systems. Strategic sectors should never rely on platforms that can be weaponized politically.

Tim Wu’s warning is not that extraction is evil, but that it is inevitable when systems grow unchecked. The antidote is not nostalgia or protectionism, but structural counterweights. Open source, sovereign infrastructure, and European-hosted AI are not ideological statements , they are those counterweights.

The tools already exist. The expertise exists. What has been missing is the political and economic will to treat infrastructure as destiny.

The recent signals from Washington should be read clearly, without drama but without denial. In the age of extraction, dependence is vulnerability. Europe still has time to choose a different model. one where digital power is built, shared, and governed at home, rather than extracted elsewhere.